羅賓漢(Robin Hood)是所謂 "創投慈善事業"(Venture Philanthropy)的先驅.

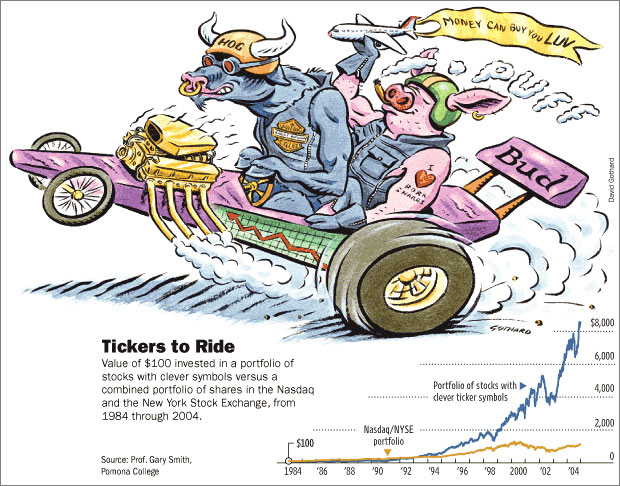

Venture Philanthropy 完全擁抱自由市場原則. 他們使用一套統一的"科學計量方法"來公平的評估每一個計畫的成效. 他們用的方法很簡單,每一塊錢的"投資"導致將來受幫助窮人加起來可賺回來的錢數. 使用這套方法他們可以比較兩個計畫的優劣然後將錢(有限資源)用在刀口上. 這跟他們run hedge fund的精神一樣 --- 用一個統一的定價方法在不同的asset class之間找出他們的相對價格, 然後買低賣高, 就這麼簡單.(see,你也可以開一家 hedge fund了)

通常好的project可毫無困難的拿到資源, 無效的則被無情的丟棄.

這"計量方法"對一個以"對抗貧窮"為主旨的組織久多麼proper啊. 我想, 對於其他不同目的組織應該也不難去設計一套"計量化"的方法吧. 你要開一個"廖添丁"慈善組織嗎? 我可是有很多不錯的idea喔!

The legend of Robin HoodA rebel's code

What makes Robin Hood different from other charities.

Every dollar counts

To entice donations, board members cover all administrative and staff expenses-meaning all contributions go 100% to fund programs.

Follow the metrics

Robin Hood spends more than $500,000 a year gathering data on the agencies it funds, and $300,000 on a staff economist who crunches numbers. Programs that don't satisfy their benefit/cost benchmarks are out.

Don't save your powder

Robin Hood doesn't have an endowment and doesn't want one: It aims to spend everything it raises each year.

Be cool

Poverty-fighting goals may be wonky, but Robin Hood's stylish courting of celebrities gives it unmatched cachet.

Power Players 看看這個董事名單吧!

The 28-member Robin Hood board has unmatched influence.

* Lee S. Ainslie III, Maverick Capital

* Victoria B. Bjorklund, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett

* Lloyd C. Blankfein, Goldman Sachs

* Peter F. Borish, Twinfields Capital

* Geoffrey Canada, Harlem Children's Zone

* Tom Brokaw, NBC News

* Maurice Chessa, Bedford-Stuyvesant I Have a Dream Program

* Richard L. Chilton Jr., Chilton Investment

* Steven A. Cohen, SAC Capital

* Glenn Dubin, Highbridge Capital

* Marian Wright Edelman, Children's Defense Fund

* Richard S. Fuld Jr., Lehman Brothers

* Jeffrey R. Immelt, General Electric

* Paul Tudor Jones II, Tudor Investment

* Peter Kiernan III, Cyrus Capital

* Marie-Josée Kravis, Hudson Institute

* Kenneth G. Langone, Invemed Associates

* Mary McCormick, Fund for the City of New York

* Doug Morris, Universal Music

* Daniel S. Och, Och-Ziff Capital

* Gwyneth Paltrow, Actress

* Robert Pittman, Pilot Group

* David Puth, J.P. Morgan Chase

* Diane Sawyer, ABC News

* Alan D. Schwartz, Bear Stearns

* John Sykes, MTV Networks

* Harvey Weinstein, Weinstein Co.

* Dirk Ziff, Ziff Brothers

The legend of Robin Hood

How the leaders of the hedge fund world have banded together to fight poverty - taking gobs of money from the rich, applying strict financial metrics in giving it away, and making philanthropy cool among the business elite

By Andy Serwer, Fortune senior editor-at-large

(Fortune Magazine) -- The idea behind one of the most innovative and influential philanthropic organizations of our time sprang from one of the more boneheaded macroeconomic calls ever made on Wall Street. Or as hedge fund maestro Paul Tudor Jones tells it, "The biggest error I've ever made had the best possible outcome."

The story begins in the summer of 1987. Stock prices were soaring, but so, too, were interest rates. The then 32-year-old Jones - who had made buckets of money during the go-go 1980s - was getting nervous. That September he told his investors that the stock market reminded him of 1929 and a crash was inevitable.

Even after October's brutal 23% one-day drop, Jones remained apocalyptic. He called up fellow hedge fund manager Glenn Dubin and pleaded, "It's happening. We're going into a great depression. We've got to do something about it. I want to start a foundation to help, and I'd like you to be involved."

Of course, Jones was dead wrong about a depression, but that hasn't mattered. He has gone on to become a Wall Street titan, with some $14.7 billion under management. More to the point, his brainchild, a charity called Robin Hood -which was born out of the direst predictions - has become a paragon, forging a new model for philanthropy and attracting heaps of cash from an enviable roster of high-profile benefactors.

In the broadest terms, Robin Hood does what its name suggests: It takes from the rich (especially its own board members) and gives to the poor. But even though its mission is focused-to fight poverty in New York City - and the roughly $525 million it has distributed pales in comparison to what Bill Gates and Warren Buffett have given, Robin Hood's influence is extraordinary.

Venture philanthropy

Robin Hood was a pioneer in what is now called venture philanthropy, or charity that embraces free-market forces. An early practitioner of using metrics to measure the effectiveness of grants, it is a place where strategies to alleviate urban poverty are hotly debated, ineffectual plans are coldly discarded, and its staff of 66 hatches radical new ideas.

It also has a radical approach to drumming up money. At first Robin Hood's donation base was limited mostly to friends of Jones's, which is to say, hedge fund managers like Dubin. Jones latched onto a clever financial model with obvious appeal to contributors: All the organization's administrative expenses are covered by Robin Hood's board members, meaning every penny donated goes directly to the cause.

Today Robin Hood is much more than a charitable organization. While it retains a strong hedgie flavor, its board is now a blue-chip collection of Who's Who in business and media that includes GE's (Charts) Jeffrey Immelt, ABC's Diane Sawyer, movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, and Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs (Charts), as well as leading lights from the nonprofit world like Marian Wright Edelman. Actress Gwyneth Paltrow is on the board too, and both the Rolling Stones and the Who have done fundraisers for the group.

Such connections have helped Robin Hood not only draw interest and money on a nationwide scale but become a gathering place for a new generation of rich and prominent Americans - a business and social network that reflects myriad intertwining relationships among board members, staff, grantees, and donors. As a significant benefactor of the organization puts it, "Robin Hood is like the cool table in the high school cafeteria."

It is not all fun and games. "It's a bigtime commitment," says Blankfein of his role as a board member. "These are serious, accomplished, dedicated people. They demand your brainpower." But the benefits and information can flow both ways. "I've been so impressed with the metrics they use," says GE's Immelt. "There's a lot we can learn from that for the GE Fund and the GE Foundation."

In fact, nonprofits around the country study and borrow from Robin Hood's programs, and copycats have sprung up in London and San Francisco. Perhaps most important, Robin Hood has brought the idea of philanthropy to a younger generation of superwealthy Americans who might not otherwise have considered it. Says board member Tom Brokaw: "Every community could have a Robin Hood-like operation. It wouldn't be as large or as well-heeled as New York's is, because it's like Willie Sutton said, That's where the money is. But when I talk to people in Denver and Memphis and other places and I tell them about Robin Hood, their eyes light up."

Kicking out the drug dealers

I recently ventured to the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn to meet Paul Jones at the Excellence Charter School for boys, an institution that Robin Hood supports and that in many ways reflects its workings. The school is the product of a pooling of dollars by the New York City Board of Education, Robin Hood, and Jones personally, plus contributions from a variety of corporations.

The school's physical plant, including a fabulous AstroTurf roof, would be the envy of any $30,000-a-year private school. Inside, groups of energized young teachers and little boys, kindergarten through second grade (and 100% minority), in white shirts and ties, ready themselves for the coming school year. Principal Jabali Sawicki tells me there is a 170-student waiting list.

Just a few years ago this building was a neighborhood eyesore, a symbol of all that had gone wrong in Bed-Stuy. Originally constructed in the 1880s as PS 70, and later used as a yeshiva, it became a home to drug dealers and prostitutes after a fire in the 1970s - even a venue for illegal cock fights.

Then, in 2004, another organization that Jones supports, Uncommon Schools, committed $30 million ($6 million from Jones personally) to buy and renovate the property. David Saltzman, the executive director of Robin Hood, persuaded Robert A.M. Stern, dean of the Yale School of Architecture, to design the facility, which was completed this spring. Signs throughout the school were done gratis by renowned design firm Pentagram. And Robin Hood sent a check for $150,000 for the school's operating budget. Books were donated by Scholastic (Charts) and HarperCollins, which have given a collective two million volumes to Robin Hood - and which explains why my arm is resting on a pristine copy of Harry the Dirty Dog as I interview Jones inside a classroom.

Jones, 51, who is as press-shy as he is charismatic, is said to have earned $500 million last year. He was raised in Memphis and educated at the University of Virginia, where he donated $35 million toward a new basketball arena, which opened in July. He's also invested tens of millions to build a nature preserve in Tanzania.

But it is here in Brooklyn that Jones pursues his biggest passion. "I love education because I love kids," he tells me in his assertive drawl. "If I retired, I'd love to teach second, third, or fourth grade. I also like education because I think it has the greatest multiplicative powers in terms of the ultimate good you're going to do for the hours and dollars expended."

Robin Hood gave grants to 21 charter schools as well as 24 regular public schools in 2005. "Fifteen years ago the only way you could impact inner-city kids who didn't have proper educational services was through an after-school program, which is a very poor substitute for a great school day," Jones says. "That changed because the charter movement began, and so my priorities shifted."

Don't charter schools draw precious resources away from other public schools?

Jones makes no apologies: "Charter schools are the best thing that ever happened to education in New York City because they provide competition to regular public schools and raise the bar that everyone is trying to attain. They provide thought leadership for other schools, so again there's a multiplicative impact."

The Excellence school, which falls under what Robin Hood calls its education portfolio, is one of more than 200 programs that it funds in New York City -everything from soup kitchens, job training for ex-cons, and housing for the homeless to financial service centers for the poor, where they are instructed on how to apply for the earned-income tax credit. (In 2006, Robin Hood helped poor working families claim $98 million in tax refunds.)

One of its first grantees: the Association to Benefit Children (ABC), an immaculate and warm day-care center for the city's most needy kids. ABC is also where board member Marie-Josée Kravis - economist and wife of buyout king Henry Kravis - first became enamored of Robin Hood, even after a little boy asked on her first tour what color underwear she was wearing.

Benefit to the poor per dollar of cost

Robin Hood's relationship with its grantees is not unlike that of a private-equity fund or an activist hedge fund. If the client organization is thriving, Robin Hood helps guide expansion efforts. If it is struggling, Robin Hood digs in, sending consultants and meting out advice on office space and leases, technology, legal, and HR. It has a program that matches interested businesspeople with nonprofit boards that need boosting. It will recommend new executive directors. It has solicited donations of professional services from the city's top law firms and the likes of Deloitte & Touche, GE, and Microsoft (Charts). "With Robin Hood, there is constant evaluation," says board member and grantee Geoffrey Canada, whose Harlem Children's Zone has adopted 60 blocks in Harlem. "It is a rigorous - and can be an exhaustive - process."

In some cases the evaluation is simple, and the choice is obvious. The head of a drug-treatment program is found using drugs: Goodbye. But in most cases Robin Hood relies on a complex system of metrics, which calculates the success of a grant by estimating its benefit to the poor per dollar of cost to Robin Hood, much like a business's rate of return.

Robin Hood hires an outside evaluation firm to collect data from each grantee. In 2005 it paid $552,000 to Philliber Research Associates for this service. The numbers come back to Robin Hood and are then crunched by chief program officer Michael Weinstein, an MIT-trained economist (and also a former editorial writer for the New York Times).

"We set out to compare the relative return of any two grants, no matter what their purpose, much the way an investor compares the relative return of any two investments," says Weinstein. "For most of our grants, our basic measure of success is, How much does our grant boost early adult earnings of poor individuals?" To estimate earnings, Weinstein taps into statistics and data from many sources. "A benefit/ cost ratio of five," he explains, "means that for every dollar Robin Hood contributes to the program, collective earnings of the poor individuals served by the program rise by $5. As a ratio, the benefit/cost calculation can be used to compare the value of any two grants, no matter their purpose." In effect, Weinstein is saying, his model allows Robin Hood to compare apples and oranges.

These metrics help Robin Hood identify programs that aren't worth the investment. Say it gives a grant of $150,000 a year to a charter school in Harlem that produces a benefit/cost ratio of six (i.e., every dollar Robin Hood spends on the school purportedly boosts the future earnings of the students by $6 a year). That compares with a $125,000-a-year grant that Robin Hood used to make to a Bronx afterschool program that emphasized the creative arts, which scored only a 0.6. Robin Hood supports a job-training group in Brooklyn that scores a nine, as well as one in Manhattan that scores only a 4.5. But that's because the Manhattan group serves ex-cons, so lower-paying jobs are to be expected.

Does the Robin Hood board cut grantees loose? You bet. Each year roughly 10% lose funding. "They size these agencies up in a gimlet-eyed fashion," says Tom Brokaw. "It's like going to a GE division meeting."

Is it right to treat philanthropy like a business? Or is this just another example of a free-market mentality overriding a pure sense of compassion? To hedge fund manager and former Robin Hood chairman Stan Druckenmiller, who remains a key benefactor, that's ridiculous: "If you spend a dollar on something that doesn't work, why continue? This is about trying to solve poverty, not applying Band-Aids."

Adds Marie-Josée Kravis: "Measuring is appropriate as one instrument of understanding. When you look at corporations, you don't look only at their earnings. You look at their product pipeline, the quality of their management, their labor relations-things you can't measure precisely. And it's the same in the nonprofit world. It's important to understand, to the extent that we can, how effective our dollars are."

One prison's high school

On a muggy afternoon in the middle of June, I drove to Rikers Island - New York City's massive jail complex - with Beth Navon, executive director of Robin Hood grantee Friends of Island Academy (FOIA). Robin Hood gave $350,000 this year to FOIA, which offers advice and support to youth incarcerated at Rikers.

Robin Hood also placed hedge fund manager Anne Dias Griffin, wife of Ken Griffin, who runs the mega Citadel hedge fund company in Chicago, on the FOIA board. Navon and I are met at the jail by Tongo Eisen-Martin, a FOIA staffer who has a master's degree in African-American studies from Columbia. As we descend into the bowels of the jail and surrender first our cellphones, then our IDs, my heart begins to race. I'm handed a temporary ID.

"Don't lose that, or we have to strip-search the entire jail," a guard warns me. Gotcha. One of FOIA's programs is running a high school inside Rikers, and one of those classrooms is our destination. Eisen-Martin, who teaches slam poetry, on this day decides to turn the class into a Q&A session. With me.

Immediately I'm surrounded by prisoners who grill me about the war in Iraq, Bill Gates, and racism. After an hour of nonstop questioning by what I later learn is a group of especially violent prisoners (two of the most curious happen to be alleged murderers), with no guards in sight, it's time to go. "If you can give these kids any bit of knowledge, you are helping them," Eisen-Martin tells me. "You never know what will trigger something good inside of them." I nod, but I'm wrung out and anxious to get home. Besides, I have a Robin Hood party to go to that night - an experience that couldn't be more different from Rikers.

"You gotta give, baby, give!"

"All right, who's getting indicted here?" Jon Stewart screams at the crowd of 4,000 of the New York area's wealthiest citizens, who chuckle, perhaps a bit nervously. Robin Hood's annual benefit dinner at the Jacob Javits Center, emceed by Stewart and Tom Brokaw, is considered by many the party of the year. It would be impressive enough for its very A-list crowd - everyone from Mel Karmazin to Mark Cuban to Matt Lauer - but even more remarkable is the astounding amount of money it raises.

Most charity dinners in New York are considered a smash if they bring in $1 million. Here success is measured in tens of millions. "If you are on Wall Street, particularly in hedge funds, you have to be here," says one of my tablemates.

The real action begins after Stewart's shtick, when Sotheby's Jamie Niven takes the stage to lead an auction unlike any other. The bidding-on a glam vacation package for eight to Mexico, Montana, and the Bahamas, for instance - is done with glow sticks and repeatedly hits the mid-six figures.

The power tables with the real heavy hitters - "billionaire's row," a friend calls it -are close to the stage. One table's guests have brought their primary-school-age kids and, amazingly, let the youngsters themselves bid for a package, as if it's some kind of game-even as the numbers top $300,000. (A Robin Hood board member next to me groans.) Stewart can't help a gibe: "Come on, kids, you can do better than that!"

At a break in the auction, a group of charter-school students perform a rap orchestrated by Jay-Z. "Read, baby, read," the kids chant. "You got to read, baby, read." Minutes later Paul Jones bounds up on stage and does his own Southern-man chicken-dance version: "You got to give, baby, give," Jones intones. "The more you give, the better you feel. The better you feel, the better you'll trade."

The crowd knows what's coming now: the serious money part of the auction. Robin Hood is raising funds to build a charter high school. "We are looking for a couple of $1 million bids for naming rights to the school's large facilities," announces Niven. And the sticks go up. Twelve of them. Niven and Jones then drum up 30 bids of $250,000 each for classrooms.

To reward all that giving, there's a performance by Beyoncé to end the evening. The final tally? In a single night Robin Hood hauls in $48 million. Some $20 million is earmarked for the new school - which will be matched by the board, $2.25 for each $1. And New York City schools chancellor Joel Klein, who at one point during the gala, at Jones's urging, stands and takes a bow, has said the city, in turn, will match the combined sum (as well as the amount of a tax credit). Overall, the $20 million for the school will grow to $180 million. The cost to put on the dinner? Around $5.6 million.

Robin Hood's fundraising machine is always in operation. It sells holiday cards and offers an online registry, which allows you to give a gift in someone's name to Robin Hood instead of buying a $5,000 espresso machine. Robin Hood's LemonAid program has kids from affluent families selling lemonade in Greenwich, Scarsdale, and the Hamptons. Last year it raised $120,000.

Robin Hood throws what it calls heroes' breakfasts to honor individuals who have dedicated their lives to fighting poverty - like Ellen Baxter of Broadway Housing, which provides apartments for the homeless - and to raise more dough. "Gwyneth Paltrow and I sat next to each other and cried at the last one together," Joel Klein tells me. And indeed, it's hard not to get choked up. (At the Baxter breakfast, a young woman described how she watched her mother die in a shelter before they were able to get a home.) "Stan Druckenmiller, Paul, they all cry," says a Robin Hood staffer. "You would too."

Then there are one-off events: The Rolling Stones played a benefit at Radio City Music Hall this spring, which raised $11 million - Harvey Weinstein even got the notoriously tightfisted band to donate $500,000. The Who played the Robin Hood gala in 2000. Why? "Because I adore and totally trust the people involved, like Harvey Weinstein and [Universal Music CEO] Doug Morris," says Pete Townshend. "Am I insane?" he asks. (Sure, Pete.)

Townshend continues: "[Robin Hood] reaches street level. That's all that matters to me." Townshend was also a headliner at the Concert for New York after 9/11, which, unbeknown to most, was orchestrated by a quartet of Robin Hood board members: Weinstein, Morris, John Sykes of MTV Networks, and former AOL chief Bob Pittman. "This show was a deeply disturbing event," says Townshend in an e-mail. "I was there to express rage at the terrorists and sympathy for those who died. I still believe the message we sent the world at the concert was a realistic one: We are vulnerable, but we are also incredibly strong - probably best not to f**k with us like this too often."

A society of peers

One of the most influential figures on Robin Hood's board was John F. Kennedy Jr., who died in July 1999. Brought on by Robin Hood's executive director, David Saltzman, who was a college friend at Brown, Kennedy helped entice Marie-Josée Kravis onto the board.

Tom Brokaw was drawn in after hearing Kennedy talk about Exodus House, a middle school for low-income families and a grantee of Robin Hood. After Kennedy's death, Brokaw became involved in Exodus "to kind of honor his life." Brokaw's friend Pittman then convinced the former news anchor to join Robin Hood's board. It's a small world at this altitude, and when you tick through the list of Robin Hood board members, it quickly becomes apparent that they are all connected.

Dubin was previously married to David Saltzman's sister. Tiki Barber of the New York Giants, who is on Robin Hood's leadership council, tells me he was introduced to the organization by Jonathan Tisch, whose family is an owner of the Giants - plus Barber played college football at the University of Virginia, Jones's alma mater. David Puth is a senior executive at J.P. Morgan, the bank that two years ago bought a majority stake in Glenn Dubin's hedge fund, Highbridge. And Gwyneth Paltrow and Harvey Weinstein are pals from way back.

Connections also provide Robin Hood with access to the world's hottest hedge funds. At the end of 2005 it had $177 million invested in funds run by board members Jones, Dubin, and Steven Cohen of SAC Capital as well as Eddie Lampert's ESL, Citadel, D.E. Shaw, and others.

Is it prudent or a conflict of interest for a philanthropy to invest in risky hedge funds, some managed by its own board members, many of which would be inaccessible to other charitable organizations? David Saltzman says no, and that these decisions are carefully reviewed to make sure they are consistent with regulatory guidelines.

Robin Hood's powerhouse board meets regularly four times a year at grantee sites. "When we get in a board meeting, everyone is a peer," says board member and hedge fund manager Lee Ainslie. "The people from the media, entertainment, nonprofits, and finance. No one dominates the discussion."

The vetting of grantees is painstaking and continual, in part because of the way Robin Hood's funding and disbursement works. For instance, all the money raised in one year, which in 2004 was $81 million, is doled out in the following year, in our example 2005. Yes, there is a reserve fund (the money invested with the hedgies), but there is no endowment. "Why put away money for a rainy day when it's pouring out?" asks Saltzman."New York City is arguably the richest city in the history of the world, and yet the majority of babies were born into poverty last year. Why would we keep powder dry under those circumstances?"

Some Robin Hood staffers are paid quite well-Weinstein, for one, earned some $300,000 in 2004 - although hardly what they might earn at one of the board members' hedge funds. Still, Robin Hood has attracted all manner of high-powered execs, such as Susan Sack, a former lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a onetime Goldman Sachs employee, who now helps grantees navigate the devilish New York real estate market. Others come from firms like McKinsey, PricewaterhouseCoopers, and Accenture. "These are people who could have incredibly high-paying jobs anywhere, and yet they chose to do this," says David Saltzman. "And believe me, the quality of employees here is the same as at a Tudor or a Goldman."

Several years ago a staff member proposed funding a needle exchange, where drug users could turn in old hypodermic needles for new ones (or simply pick up new ones). Fresh needles help prevent the spread of HIV/AIDs. A vigorous debate ensued on the board. "Why don't we throw in a couple of hits of acid too?" Jones asked sarcastically. But to Druckenmiller and others, the issue was a matter of money: It's far cheaper to provide free needles to addicts than it is to care for an AIDS patient.

The pros won out, and on a recent boiling-hot afternoon, I visited a needle exchange that received $350,000 from Robin Hood this year, located in a small storefront on Manhattan's Lower East Side. Drug users slouched in throughout the afternoon, selecting needles (from three sizes), works, and other neatly packaged paraphernalia. In a second room, junkies nodded off on couches in front of a TV. (They are prohibited from shooting up there.) It is a shocking and powerful scene, and yet to supporters of the program, absolutely necessary.

The evidence they cite: In 1992 the HIV rate among New York City drug addicts was 52%. Subsequently, needle exchanges were introduced, and now the rate is 14%. "I have a soft spot for children's programs," says Glenn Dubin, "but the needle-exchange program also resonates with me because I think we did something very bold."

Keep your checkbook open

"I grew up in Washington Heights, so I do feel a real affinity with the work that we're doing," Dubin says. For Paul Jones, an out-of-towner, the motivation is slightly different: "All my success was gained basically in New York City, and this was my way of repaying New York. I couldn't have done what I did anywhere else in the world."

Jones's gift extends well beyond the tens of millions of dollars in checks he's written. "Paul's genius was that he created an organization that didn't have his name on the door to make it easier for him to entice people to join Robin Hood, not only for their money but also to contribute their time, energy, and brainpower," says David Saltzman. "It wasn't about his ego - it was about trying to do good."

Folks at Robin Hood insist that their mission has just begun. They say that one in every five New Yorkers lives in poverty and that the foundation must get bigger to meet this challenge. That means raising more money. And they know how to push for it.

One Robin Hood supporter who'd had a particularly good year says he was told that there were no $30,000 tables available for this year's benefit dinner, only $50,000 tables. "They wanted him to step up," says a colleague and fellow Robin Hood supporter. "I think they keep tabs on how well we are doing."

According to board member Ainslie, there are also new fundraising sources to be tapped-executives in real estate and Fortune 500 companies, for instance. "When we tell people their dollars are going to help their city, that every cent goes to those in need, that the board pays expenses, and that we hold our grantees accountable, you are talking about very powerful selling points," he says.

Robin Hood will need them, because with each year the organization gets in deeper and deeper. Robin Hood's momentum will continue to push the group forward. With huge capital projects like the Excellence school, simply maintaining these facilities will cost millions more each year. "Poverty is a growth business," Jones tells me. The good news is it seems that the best and brightest minds on Wall Street and in business are starting to do something about it.

Reporter associate Corey Hajim contributed to this story.